Russia has seen a dramatic hike in the prosecutions of the internet users

By Daria Luganskaia

Andrei Bubeyev, a 41-year-old mechanical engineer from a provincial Russian city Tver, was not an influential blogger. Yet he went to prison for his online activity. Bubeyev had only 12 friends on the social network Vkontakte by 5 May 2016, the day when he was sent to penal colony for two years and three months for eight reposts he had made on his page.

“Like most of us”

The reposts were mostly about the recent conflict between Russia and Ukraine and relations between those two countries, a Russian online media Meduza reported. He shared posts from accounts of multiple activist groups, often pro-Ukrainian and right-wing, such as “Azov” or “The news of Russian world”. One of the shared materials was about returning Crimea Peninsula, the territory of Ukraine annexed by Russia in 2014, back to Kiev.

But it would be wrong to say that the investigation was solely concerned about anything related to Ukraine. Among other things, they attached to his case an aggressive repost – a photo with a knife covered by blood with a sentence: “It is worth knowing that rotation of the knife in the wound increases the possibility of death by 90%”.

His wife, Anastasia, left alone with a four-year-old child, writes RuNet Explorer in a message on Vkontakte:

“Andrei was not an activist or politician of any kind. Just an ordinary user of social networks, like most of us. He used his page on Vkontakte as a notebook, keeping interesting news and stories at hand. He did want to influence anybody.”

A court in Tver ruled out that those eight shares contained extremism and “calls for violation of the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation”.

His wife continues: “We filed an appeal against the sentence, but the ruling is not due until August.Andrei has already spent more than a year in jail, most of the time in an area with video surveillance. He is locked with the people who have committed serious crimes. Any attempt to transfer someone sitting in this area food and other things results in the placement in a punishment cell for a week. Family visits are not allowed. We have not talked to him since December 2015. All we had are letters and short meetings in the courtroom.”

Anastasia felt her life was falling apart after his arrest:

“We are each other’s best friends. He is my main support in life. And when this support was brutally torn, everything went wrong. I could not eat, could not sleep.” She has to quit her studies and find a part-time job at an advertisement agency as a promoter. Now Anastasia spends her time handing passer-bys leaflets or organising degustations to support herself and a little child. “It’s not even funny: he was charged for extremist calls he’ve made to 12 friends who were not even interested in politic.”

What is extremism?

Extremism is a vague term adopted in a number of Russian laws. The notion of extremism is very broad, thereby it can be used in many cases, sometimes, unlawfully. A radical nationalist as well as an influential investigative blogger or even a full-time correspondent of a prominent national newspaper were convicted of extremism. Actually, the extremism legislations contain no certain definition of extremism. Instead, there is a long list of so-called extremist activities.

What is extremism according to the Russian law?● forcible change of the foundations of the constitutional system and violation of integrity of the Russian Federation; ● public justification of terrorism and other terrorist activity; ● incitement of social, racial, ethnic or religious hatred; ● propaganda of exclusiveness, superiority or inferiority of an individual based on his/her social, racial, ethnic, religious or linguistic identity, or his/her attitude to religion; ● violation of rights and legitimate interests of an individual because of his/her social, racial, ethnic, religious or linguistic identity or attitude to religion; ● preventing citizens from exercising their electoral rights and the right to participate in a referendum, or violating the secrecy of the vote, combined with violence or threats to use violence; ● preventing legitimate activities of government authorities, local self-government, election commissions, public and religious associations or other organizations, combined with violence or threats to use violence; ● committing crimes involving the aggravating factors listed in article 63(1) of the Criminal Code (e.g., repeated crimes, crimes committed by an organized group, or crimes with severe consequences); ● propaganda and public demonstration of Nazi attributes or symbols, or attributes and symbols similar to them or public demonstration of attributes or symbols of extremist organizations; ● mass distribution of materials known to be extremist, their production and possession for the purposes of distribution; ● dissemination of knowingly false accusations against federal or regional officials in their official capacity, alleging that they have committed illegal or criminal acts; ● organization and preparation of extremist acts, and calls to commit them; and financing the above-mentioned acts or providing any other material support to an extremist organization, including assistance in printing their materials, offering educational or technical facilities, or providing communications or information services. |

The list of extremist activities has expanded in recent years.

Senior Advisor at OSCE Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media Andrei Richter explains to RuNet Explorer:

“Originally the notion of extremism in Russia was based on a belief that terrorists were essentially victims of radical and extremist ideas. It was expressed in such a way in the federal law “on the counteraction of extremist activity” in 2002. At first, the lawmakers simply transferred the provisions of existed Article 282 to a new legislation: incitement of national, racial or religious enmity, the humiliation of national dignity, and also propaganda of exceptionalism, superiority or inferiority of citizens on grounds of their religion, nationality or race.”

Later on, the list of extremist activities was enlarged twice.

Hard times for bloggers

Andrey Bubeyev is just one of a number of internet users that have been recently put behind the bars in Russia. This harsh punishment is new phenomenon even for Russia, the country ranked by an American NGO Freedom House as “Not free” in its latest report on the freedom on the Internet. According to Soldatov,the co-author Red Web, a book about the attack on internet freedom in Russia published in 2015, such regulation is very strict in comparison to the European or American law.

The lawmakers in Russia suggested amendments to the criminal code setting penalties of up to five years in prison for publishing extremist content online in 2014. And soon this bill became a law. Since the end of 2015, the courts in Russia started to issue prison sentences for words. Previously, the toughest punishment one could receive for such actions was a suspended sentence but usually people paid fines.

Andrei Soldatov says:

“Nobody expected that the authorities would threaten people by issuing non-suspended sentences. It is the scariest thing that happened with the internet in Russia in recent months.”

SOVA Center for Information and Analysis, a Moscow-based nonprofit, recorded that at least 17 people were imprisoned for something they published online from June 2015 until June 2016. This NGO conducts researches on nationalism and racism, relations between the churches and secular society, political radicalism, human rights issues, especially government misuse of anti-extremism laws.

The director of this centre Alexander Verhovsky stresses that “17 is a large number”. “Earlier, such sentences were sporadic. Only two people went to prison for things they published or shared online last year,” he says to RuNet Explorer. Moreover, 17 is not the final figure: SOVA Center for Information and Analysis is still working on the latest report which is due in the end of July.

Verhovsky notices that those cases are different. Some people are actually very violent in their words.In some cases, the expert understands the reasons for sending dangerous people to prison. “Frankly, I would have issued a prison sentence to some people if I were a judge. There are those with ultra-left views or people calling for murders,” Verhovsky confesses.

He labels only two of these 17 cases as the abuse of human rights and acts of censorship.

The first incident happened with a female activist from a southern city Krasnodar, Darya Polyudova. This girl was sentenced to two years in a penal colony for “public calls to separatism and extremism” after several incidents. In April 2014, she went on a single-person picket with a banner against the war in Ukraine and in support of a revolution in Russia. Later she posted on her Vkontakte page messages about revolution calling “to fight Putin with his own weapons” and mentioning the Russian Kuban region as a historically ethnic Ukrainian territory.

The second case happened in the eastern part of the country, in the Tatarstan Republic. Rafis Kashapov, the chairman of the Naberezhnochelinsky Tatar Public Centre, has been charged under part 1, article 282 (inciting hatred or enmity). He published three texts and a photo collage on Vkontakte that sharply criticised Russia’s foreign policy in relation to Ukraine and, in particular in connection with the annexation of Crimea.

He is kept in custody in Kazan, the capital of Tatarstan. Memorial, a prominent Moscow-based NGO, considers him a political prisoner. Established in 1989, this civil rights society focuses on finding and publicizing information about the Soviet Union’s totalitarian past, primarily about victims or repressions. But they also monitor human rights in Russia and other post-Soviet countries.

Memorial, however, consider another person recently accused of extremism a political prisoner. Alexander Sokolov, a journalist of RBC, was detained in July 2015 on suspicion of extremism. Investigators alleged he and two associates, Valery Parfyonov and Yury Mukhin, worked on the program of the left-wing movement People’s Will Army despite its prohibition in 2010. According to investigators, they renamed the organization and kept the same goals, in particular, organizing a referendum that would destabilize the country. The ground for the case was a YouTube video with a general speaking at a Victory Day in 2012 that Sokolov posted.

The journalist claimed he was not guilty and said the investigation was linked to his professional activities. He conducted anti-corruption investigations at RBC and wrote a thesis about corruption related to Olympics 2014 held in Russian city Sochi.

Sokolov has been kept in custody. In the end of May, he filed an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights. His defense stressed that the prosecution was caused by his investigative work, and the arrest as a preventive measure does not correspond to the nature of the offense, moreover, it was extended several times despite their appeals.

Other cases that SOVA Center for Information and Analysis does not call unlawful are mostly about nationalists. Vadim Tyumentsev, a blogger with radically nationalist views, uploaded two videos of himself to YouTube and Vkontakte. In one of the videos, he criticized pro-Kremlin separatists in eastern Ukraine and suggested that local authorities should “expel Donetsk and Lugansk refugees from the region”.

However, the second video had a different nature. The blogger sharply criticized the local authorities and appeal people to attend an unsanctioned meeting to protest against a rise in local bus fares. In the end, he was convicted of publishing hate speech and calls for extremism online and sentenced to five years in prison for both videos.

Another blogger, Oleg Novozhenin from the Siberian town of Surgut, supported the actions of the Ukrainian nationalist party “Right Sector” and the right-wing “Azov” battalion in his videos. He was sentenced to a one-year imprisonment in a penal colony.

For the thoughts of others

Russian anti-extremist legislation is designed in a way that it does not matter for if there is a real harm to the public in anti-extremist cases.

Andrei Richter explains:

“Russian anti-extremism regulation differs from international practice and standards, such as the case of the European Court of Human Rights, by giving the ability to punish for extremism which does not entail abuse or discrimination of people.”

SOVA Center for Information and Analysis is concerned about the case of Andrei Bubeyev, for instance, because he did not influence the public. “If you stretch the law a little bit, you can actually find that those reposts Andrey Bubeyev had made could fell under the current legislation. But he had a small audience, subsequently, the public danger of those shares was close to zero,” Verhovsky says.

The Russian legislation does not divide responsibility for the original publication and a retweet or other form of sharing anything either. Eventually, anyone could be prosecuted for the words of others, such as a link to a publication revealing “personal privacy”, containing defamation, or calls for an unauthorized rally.

A lawyer specialised on the regulation of the internet Sarkis Darbinyan says to RuNet Explorer:

“Anyone could sue a user for a repost – a legal entity or a person. The security forces themselves are monitoring social networks, looking for provocative material through the line “search” or track specific users. Specifically, they “love” social network VKontakte.”

Tougher from year to year

More and more people in Russia are accused of extremism from year to year. According to the data by SOVA Center for Information and Analysis, 82 people were charged with extremism in 2011. In 2015, their number reached 369 people. In other words, over the past five years, the number of criminal prosecutions for internet extremism has grown by 350 per cent.

More than half of those cases were against people under the age of 25. Many of those convicted are ordinary people whose cases went unnoticed by the media. Moreover, the number of such sentences issued to opposition activists is also expanding.

Before 2015, the internet users were charged with fines or given suspended sentences. Any websites of media organisations are facing fines or bans for extremism. IInterestingly they are punished without a trial. Federal law 398 known as “Lugovoi’s law” (named after its author, deputy of the lower house of parliament, Andrei Luguvoy) allows authorities to block websites for extremism on the orders of the Prosecutor General Office without a court order. If the office of the General Prosecutor or the regulatory body Roskomnadzor finds that some content on the website is extremist, they give a website owner 24 hours to delete it. Otherwise, its IP-address will be banned.

There is a special legislation designed for media. If a website is registered as “mass media”, Roskomnadzor, has an additional right to issue warnings to its management about “abuse of freedom of mass media” in accordance with Article 4 of the law “On Mass Media”. It means that media would be punished for extremism, incitement of terrorism, propaganda of violence and cruelty, propaganda of drug abuse, or obscene language. If a mass media website receives two warnings in one year, Roskomnadzor will cancel its license.

RBC, a nationwide business news media group, and nine other media received such a warning for publishing the cover of the Charlie Hebdo issue with the prophet Muhammed labeled as extremism.

It is also getting harder to defend people in anti-extremist cases. Back in 2009, Andrei Richter, then a lecturer at the Lomonosov Moscow State University, the oldest and the most prestigious Russian university, started his course on media law with an episode from South Park series. “All the students were amused. We did not expect a lecture to entertain us with South Park,” recalls Ogannes Gasparyan, a television producer and then a student of the international journalism department.

Actually, Richter played this animation to explain why he had decided that this animation was not extremist in any way. He wrote a content analyses of that episode for the proceedings against South Park. The court agreed with his expertise in the end, and this animation remained on screens.

The case against South Park was an administrative, not a criminal one. The court verdicts in such cases could be still justificatory. But the statistics in criminal cases is very different. “In 2015, there was only one justificatory decision in the anti-extremist case,” the director of SOVA Center for Information and Analysis warns.

To tweet or not no tweet?

A prison sentence for extremism, however, is just one of several threats the Russian internet users may face. There are lots of rules in the online presence that every citizen is obliged to follow nowadays.

The Russian law has penalties for

- defamation (Article 128.1 of the criminal code)

- defamation against a judge or prosecutor (Article 298.1)

- insulting the authorities (Article 319)

- calls for terrorism (Article 205.1)

- insulting religious feelings (Article 148)

- calls for extremism (Article 280)

- calls for separatism (Article 280.1)

- incitement of hatred (Article 282)

- spreading false information on the activities of the Soviet Union in World War II (Article 354.1)

- displaying Nazi symbols or symbols of organizations deemed extremist (Article 20.3 of the administrative code)

- the dissemination of extremist materials (Article 20.29), or insult (Article 5.61).

Russian internet users should also keep an eye on the news about upcoming legislations. The government is also trying to figure out a way to control traffic going through circumvention tools, or anonymizers such as Tor. They let users stay anonymous and access banned websites.

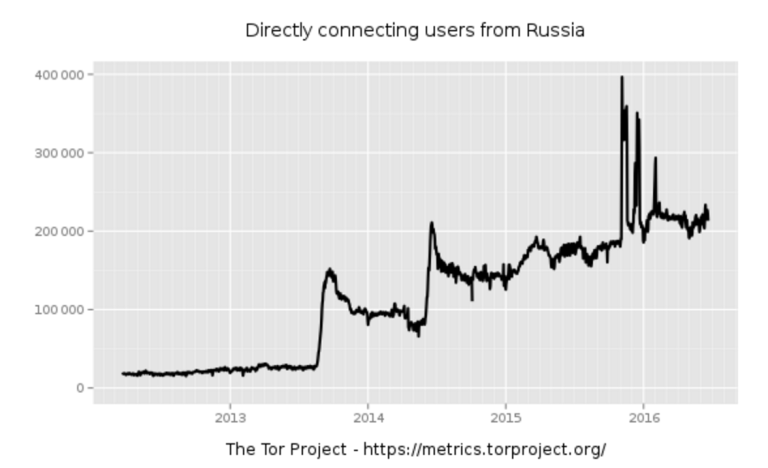

The popularity of such tools is growing in Russia at a rocket pace. According to the data published by Tor, two years ago, Russia was only the eighth country by the number of users directly connected to Tor. In the end of May 2016, Russia was ranked the second one following the US. There is data representing growing interest to anonymizers in Russia. According to Yandex, the number of search inquiries about VPN (virtual private network)increased from 137,000 in March 2014 to 184,000 in February 2016.

“They [Russian authorities] do not know how to deal with it. There were just a few geeky Tor users, and now it is a commonplace technology,” Andrei Soldatov believes.

Why are the Russians getting into anonymizers? Soldatov thinks the main reason is their love for free films and other content: “They blocked Rutracker.org [very popular torrent tracker in Russia] and then the rise began.” Rutracker.org is banned in Russia since January 2016. Irina Levova, an analyst of the Russian Association for Electronic Communications, holds a different opinion:

“Why shouldn’t Russia be among the leaders on Tor with such draconian laws regulating the internet?”

First, the authorities tried to ban a website for spreading information about anonymizers was implemented. A city court in Anapa, a city in southern Russia, handed out a precedential verdict in the case against RosComSvododa, a nonprofit monitoring banned content.

The court ruled an article with instructions on how to use anonymizers to access banned information was illegal. RosComSvododa could have been banned entirely but its activists found a loop in the system. They published an official answer from the Ministry of Telecom and Mass Communications saying that their article about anonymizers does not break the law.

However, the same governmental body, Ministry of Telecom and Mass Communications proposed a draft bill suggesting that the telecom operators should be responsible for dissemination of the information about anonymizers in May 2016.

The internet providers could face a fine if the website they operate would publish “propaganda” of the usage of anonymizers. It was the second edition of this proposal. The previous version of a draft on anonymizers was written under Roskomnadzor’s guidance and implied fines imposed directly onto users.

Interestingly, just a couple of months before that, the regulator had held a different position about anonymizers. In February, Roskomnadzor stated they did not plan to block anonymizers because they are “legal technologies” but plan to approach the administration of this services instead.

Beyond the law

Except for legal prosecution, the internet users may face pressure from those in power. A prominent political correspondent and columnist Oleg Kashin was nearly killed in 2010 for a comment he made on LiveJournal. He was beaten with a steel pipe next to his home. Badly injured with a finger missing, he later recovered in a hospital.

After five years of investigation, the police named the men who were officially accused of this crime – Danila Veselov and Mikhail Kavtaskin, employees of a plant that belongs to “Leninets”, a holding owned by Anatoly Turchak, a friend of President Putin and a father of the Pskov region Governor Andrei Turchak. The accused told the police Gorbunov asked them to commit this crime following an offensive comment about the Pskov regional governor, Andrey Turchak, that Kashin left under a post on LiveJournal. However, Turchak has never been questioned. He called the allegations “a provocation” and kept his position as the governor.

This case shows that journalists and bloggers are not protected by law.

Oleg Kashin published an open letter to president Vladimir Putin and prime minister Dmitry Medvedev:

“The last 15 years haven’t been a revival for Russia, and the country hasn’t risen from its knees. This time has been a monumental moral catastrophe for our generation. And both of you, Mr Putin and Mr Medvedev, are personally responsible for it.

In Russian society today, even obvious questions about good and evil have become impossible. Is it OK to steal? Is it OK to cheat? Is murder ethical? With each of these questions, it’s become customary in Russia now to answer that things aren’t so simple. All your good works have left the nation demoralised and disoriented.”